Universal Bitcoin Income

David Bailey, the head of Bitcoin Magazine, recently posted a tweet wondering how feasible a Universal Basic Income (UBI) program in the U.S. would be using Bitcoin.

Bailey framed this as a thought experiment aimed at bridging the gap between the prototypical UBI proponents, who favor equity, and Bitcoiners, who tend to value meritocracy. Could a Bitcoin-based UBI make both sides appreciate each other a little more?

Running some quick numbers, Bailey quickly realized that implementing such a system with Bitcoin would be practically impossible due to the limitations imposed by its protocol. Bitcoin has a fixed supply and makes forced extraction difficult. This means that all distributed income would have to come from government (or whoever manages the UBI system) revenues in the form of taxes or debt, as forcibly extracting Bitcoin from unwilling citizens would be challenging. Both of these limitations torpedo the system’s long-term viability.

Those who were hopefully waiting for the government to send them Bitcoin every month just for breathing in and out might be better off spending their time on other endeavors, wouldn’t they?

Meanwhile, we can dedicate our time to studying the origins of the UBI idea: Why is UBI associated with the left, progressivism, and social justice proponents? I know there are Bitcoiners who believe in UBI as a solution to social problems. Could we find a UBI system aligned with the libertarian ideas that inspire Bitcoin?

To study this question, we must start in Rome, around the year 123 BCE.

That year, Gaius Sempronius Gracchus came to power in Rome, succeeding his brother Tiberius. These were difficult years in Rome, the prelude to the civil wars between Marius, Sulla, and others. Whereas the civil wars revealed to the common people the power of having the army’s favor, the years surrounding the Gracchi brothers' rule demonstrated the power of populism.

Until the 2nd century BCE, Rome had been a society of small landowners who worked their own land. This provided Rome with two advantages: employment for the people and a food supply close to the great city. Years of victories and foreign wealth began to change this. Many small landowners chose to abandon the harsh life of farming to enjoy the big city, and Rome’s countryside gradually turned into large estates worked by slaves. This, of course, posed two problems for Rome: fewer jobs for the people and less than professional farming. The combination of these problems led to widespread discontent and created a new political strategy for Roman politicians: food in exchange for support.

Gaius Gracchus came to power with a reformist speech aimed primarily at the common people. In his first year, he introduced several measures to replicate the Greek democratic system in Rome. One of them, not the most famous at the time and initially intended as a temporary measure, ended up surviving the Republic and becoming part of Rome’s history: the grain law. This law required the state to sell grain to citizens below market price. Essentially, it was the beginning of what later became a form of UBI in the form of bread and wine for Roman citizens. This income came from resources taken from Rome’s provinces.

The spirit of the measure can be traced back to Ancient Greece, which, as historian Rostovtzeff explains in his book Rome, held the belief that citizens had the right to partake in the state's revenues—essentially, to use public money for their maintenance and comfort.

To many scholars of the Roman period, the state’s ability to provide bread and wine to some 200,000 citizens year after year, century after century, might have seemed admirable and a sign of progress. However, one might ask whether this solution truly benefited the people or if they would have been better off without it. On one hand, the meager sustenance in Rome meant that the barbarians across the Rhine were often better fed than many Roman citizens. On the other hand, the availability of free (though limited) food may have encouraged many to stay in Rome despite having better prospects elsewhere. We will never know what it could have been.

Undoubtedly inspired by Rome’s progress, Thomas More wrote Utopia in 1516, a book that presents a society where UBI, as we know it, doesn’t exist but its foundational ideas do.

More’s utopian society was one where citizens’ basic needs were met, there was no private property (an idea not seen in Rome until the rise of Christianity, a faith More himself followed), goods were distributed equally among citizens, and everyone worked six hours a day. A communist-tinged utopia that undoubtedly helped associate the idea of UBI with the political left as we understand it today.

However, not all thinkers who saw the utility of UBI approached it from an equity-based perspective. Another Thomas, this one known for his libertarian ideas, also proposed a form of UBI.

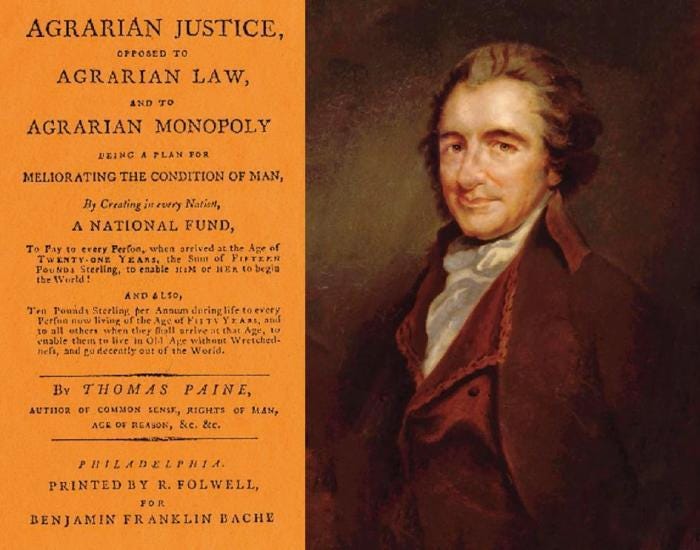

Thomas Paine, one of the Founding Fathers of the U.S., is known for his pamphlet Common Sense, published in 1776, which advocated for the American colonies’ independence from Britain.

Many of Paine’s ideas could be considered libertarian today (libertarianism as a formal ideology would emerge much later). For example, Paine believed in minimal government and stated that "government, even in its best state, is but a necessary evil; in its worst state, an intolerable one." He staunchly defended individual liberties, including freedom of religion and speech. And along with these, what he saw as the natural rights of individuals: life, liberty, and property. But when it came to property, alas, not too much of it.

This is where we find the concept of UBI in Paine’s thinking.

One of his lesser-known works, Agrarian Justice, proposed a system for redistributing the land that had become communal property after the American Revolution. Paine detailed a plan to tax landowners once per generation to fund the needs of those without land. Essentially, he suggested taxing inheritances to finance pensions for the elderly and provide a one-time payment to citizens upon reaching adulthood. In Paine’s view, property should be private but serve society.

Specifically, Paine proposed a 10% inheritance tax. Under this plan, after six generations, a family’s wealth would be reduced to less than half its original amount. This was Paine’s method for redistributing wealth and preventing its accumulation in a few hands—one that clashes with his defense of private property but at least explains how to fund a UBI system. That said, its effectiveness would be questionable. The tax could be avoided through donations, trusts, etc. Still, it's a good example of how UBI doesn’t necessarily stem from an equity-driven, progressive framework.

Examples like Paine’s or Bitcoiners advocating for UBI make me think that it isn’t a progressive mindset that underpins the idea. This historical review allows us to see that the common denominator behind UBI ideas isn’t ideology but a very particular circumstance: unexpectedly found wealth.

From Ancient Rome to last month, dozens of UBI programs have been theorized and tested in various forms. All of them have been launched because a republic, kingdom, state, or peoples stumbled upon a source of wealth. In Rome, it was the conquest of lands rich in grain, slaves, and gold that allowed Gaius to provide nearly free grain; Paine based his income plan on lands taken from the British Crown, and modern societies rely on the apparent inexhaustibility of fiat money and the disregard for sovereign debt repayment to experiment with UBI systems.

There’s no real-world scenario—except a utopian one—where something valuable can be given continuously without expecting anything in return. Of course, all modern UBI pilots try to figure out how to create a perpetual motion system, where 100 units of value enter citizens’ pockets and generate another 100 to sustain the system without external input. So far, their success rate is about the same as that of perpetual motion machines.

To prepare this article, I have read the results of several of these UBI pilot programs and watched videos on the subject. Two of the most interesting ones were conducted recently by OpenAI and the Roosevelt Institute, respectively. However, I ended up not using any of this analysis because they all fail in their attempt to generate as much wealth as they extract to finance themselves, which prevents them from moving beyond the experimental phase.

Interestingly, the conclusion I have reached is that Bitcoin is probably the only protocol under which a sustainable UBI system could be implemented. This epiphany came to me while reading about the original idea behind UBI plans—the one that inspired Gaius Gracchus to launch his grain law in Rome. If you recall, in Ancient Greece, it was understood that citizens should be able to “participate at will in the state’s revenues,” so if the state generated wealth, citizens should have access to it for their maintenance and well-being.

Beyond whether implementing such a system would be good or bad (I am personally against it due to incentive issues, though I see cases where it could be temporarily beneficial), Bitcoin seems to me to be the perfect system for a UBI precisely because of the two properties mentioned at the beginning: its fixed supply and resistance to confiscation. If we agree that the problem with UBIs is that they rely on an external source of wealth (plundering other lands, making them unsustainable) or an internal one (inflation or property seizures, also unsustainable), Bitcoin’s confiscation resistance makes it the ideal candidate. Since it does not allow for confiscation or inflation, any UBI system built on Bitcoin would always be voluntary and likely conditional.

Citizens holding Bitcoin balances would decide on a tax level they felt comfortable with and contribute it to the government. The government would find it difficult to impose levies or seize assets from its citizens or from other realms, meaning the system would always be based on negotiated equality. At the same time, citizens would have perfect information about the state’s wealth and would be rightful claimants to it for their maintenance.

True, it wouldn’t be universal (as I stated at the beginning!), but it would be sustainable.